Oh, to be anonymous again. To be a nobody. What a gift.

This is what I thought to myself sitting here in Barcelona after a few weeks in Ghana. I had been at the cafe for hours and was able to feign Spaniard using a few Spanish words, mumbled confidently. It was intoxicating to disappear, accidentally as it may have been, for a few hours.

The thing is, as a white person visiting Ghana you will be the center of attention. You, the village spectacle — the obroni — loved (sort of) suspiciously (mainly) but considered unquestionably transient (are you even really there?), if curious, and most definitely not part of the natural landscape.

This is different than the experience of outsider-ness in Japan. In Japan you, too, are a spectacle — hesitantly welcomed, probably transient, quite certain of your thereness. But the distance between the observed and the observer is much closer in a country like Japan. In Japan you may not understand each other wholly, but the ability to get there — to bridge the cultural gap — feels attainable. Like fording a river. In Ghana that gap is like the Grand Canyon.

Obroni! Obroni! scream the children.1 They are as cute as any cute kid you’ve ever seen. And the banality strikes you that, yes, children are as children are, wherever you may go. That we all really do start off on some universal footing. That, sure, they’re in a market, and will likely work in a market, maybe die in or near a market (I know, I know: too presumptuous) but that they could have just as well been rocket scientists had they been born in, say, Berkeley. And you make faces at these could-be-rocketeers and they giggle and you walk towards them and they run away. Again, they run to you and you make more faces causing more giggles. You chase them a bit and they scream in delight and scamper off, running between bolts of colorful cloth, diving under tables, hiding behind parents — big parents — working, sewing. And then — then the canyon emerges: A mother, seeing this, delighted, laughing, grabs the arm of her little girl (three years old? four?) and swings her like a rag-doll (my god!) and stands, laughing maniacally, thinking this is how you partake in obroni fun, and begins to deliver her daughter, now screaming in terror, to you, the long nosed, hairy armed monster. You smile all-teeth-no-eyes and make no no no gestures with your hands — I don’t want your daughter! — as you back away and force a laugh but the mother is insistent. She will give you her child, ha ha! By the time she reaches you the little girl is mortified, face contorted with fear, drowning in saltwater tears, so afraid (forever?) of the obroni.

Eventually she’s released and runs under a far away sewing machine, shaking, or so you imagine. You and the mother snap fingers as is the custom and you make approving noises and scrunch your face in approving ways, nodding. Oh yes yes that was good good job yes yes what fun indeed.

You return to shopping for shirts you know you won’t wear2 with a bit of a heavy heart. Sad you made a small girl cry. Or, if not you directly, then the presence of you — the incongruity of your market walk.

You buy some cloth and walk around a bit more. Everyone sees you. You are anything but invisible. You turn another corner and there she is — the girl — sitting on her mother’s lap at the sewing machine, laughing with her, her face still smeared with the mixture of tears and dust. You walk by and make a silly face and they both laugh. The little girl does not dive under the machine. Does not scream in horror. She keeps laughing and waves and you are able to leave with a lighter heart.

Weeks later I am in that Spanish cafe and think to myself:

Oh, to be anonymous again. To be a nobody. What a gift.

As I think this a mother comes in with a child in tow, and the child screams and makes noises, the child demands things and the mother sticks some cake in its mouth, but never once does the child even see me there, never once does it yell out or point or treat me like a spectacle. I am invisible once again and that is a wonderful thing, indeed.

-

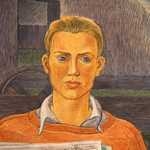

You can see some of them up in the photo above — they’re just behind the shoulder of that man, peeking at me, getting ready to run off as soon as I acknowledge them. ↩

-

Oh, you wish you’d wear them, these colorful African shirts, but right now, on vacation, you’re full-on high off the dust in the air and the wild food and the women having their hair braided in dark stalls. And the chances of you making a rational decision that will transfer out of Africa into the rest of your universe is very low indeed. ↩