Hitotoki

New York Tales from Curious Borough Dwellers- Tokyo (en)

- Tokyo (ja)

- New York (ny)

- London

- Paris

- Shanghai

- Sofia

“His almost-loss was my almost- nonexistence.”

Two guys had gotten to the restaurant just seconds before me, and they were already eating their summer rolls. I like to think that I’m the kind of person who doesn’t resent someone else eating, but Hanco’s is like that: you can’t have people on line in front of you, because it’s going to take a while. So there it was, the squeak of the door, the backs of their heads while we’d stood on line, then me waiting for my shredded chicken sandwich and bubble tea on a lawn chair next to a mustard-green wall.

How easily chance might have stopped these two along the way to look at an accident, a bird or a personalized license plate[1]; then I’d have been there first, eating. Could I have grabbed my keys and been out the door quicker? Probably. But who knew that seconds mattered here? Chance is funny like that.

There was a security camera pointed at me, or, more precisely, at the door behind me. The old wood-framed slab opened onto a hallway years ago. Now it was sealed shut with thick coats of that mustard-green paint. Everything is layered in the brownstones that line this block of Bergen Street.

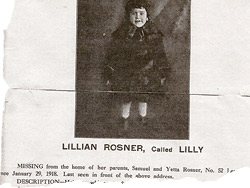

Years ago, a childless woman snatched a little girl off of a Harlem sidewalk and took her down here to a boarding house a couple of doors down from what’s now the Vietnamese sandwich shop. It only lasted a few cold, winter days. Someone spotted the three-year old girl—my grandmother-to-be—and tipped off the police, who took my great grandfather down here to 101 Bergen Street to claim her.

My young grandmother “ran to ‘Papa’ with open arms,” according to The New York Times of February 4, 1918[2]. Another paper[3] gives more detail here, saying that my great grandfather’s “face work[ed] convulsively. He opened his mouth as if to speak, but no words came. He did not even hold out his arms. He just stood there.”

I don’t know if he should have gasped with relief, cried at what could have been, jumped up and down, spit at the woman, kicked his heels, or, at the very least, if he should have held out his arms for the daughter he’d thought he’d lost. How should a person act when something like that happens? And what about the rest of the time, when things are, or seem to be, normal? His almost-loss was my almost-nonexistence.

And was my grandmother’s kidnapper happy those few days that she thought she had a daughter? Was her loneliness quenched when she led the little girl down the sidewalk—past the storefront where the girl’s grandson would someday buy Vietnamese sandwiches—cupping little Lillian’s hand in her own to keep it warm in the late-January chill?

I looked at the security camera looking at me. By chance it had recorded this moment.

referenced works

- So many possibilities. We like ICEMAN, like the Don Caballero song, but there's also the ASSMAN variation from Seinfeld. ↩

- Read a pdf of the story, Girl Detective Finds Rosner Girl; Discovers Kidnapped Child with Strange Woman in Brooklyn Lodging House, at nytimes.com's archives. ↩

- Perhaps the defunct Herald-Tribune? Our clippings cut off the top of the page. We checked the Brooklyn Eagle and it's not that. ↩

location information

- Name: Hanco's Bubble Tea & Vietnamese

- Address: 85 Bergen St., Brooklyn NY 11201

- Time of story: afternoon

- Latitude: 40.686659

- Longitude: -73.990294

- Map: Google Maps

commentary